-

Calendar 2024

Calendar 2023

Calendar 2022

Calendar 2021

Calendar 2020

-

Children of Ginko – Preview

31 October, Shanghai

-

Children of Ginko – Premiere

7-8 November, Shanghai,

Calendar 2019

-

Dance Dramaturgy 2.1

23-23 April, Aosai Space, Dali

-

New Text New Stage – “A Deal” Australian Premiere

23-31 August, Sydney

Calendar 2018

-

Web Traffic — A Multimedia Dance Theatre

Jan.5-7th , Shanghai International Dance Center

-

China ComingOUT – Creative Writing for LGBTQ Youth

31st Jan.-4th Feb. , Destination, Beijing.

-

SPEAK OUT: #1 LGBTQ&Perfromance BJ

7th, April , Italian Institute of Culture, Beijing

-

SPEAK OUT: #2 Performance&Performativity

8th, April , Xiaozhong Bookstore, Beijing

-

SPEAK OUT: #1 LGBTQ&Perfromance SH

10th, April , NEXTMIXING, Shanghai

-

SPEAK OUT: #1 LGBTQ&Perfromance GZ

12th, April , Ergao Dance Production Group, Guangzhou

-

SPEAK OUT : #3 Gender, Documentary and Activism

19th, May, Bookworm, Beijing

-

China ComingOUT – Creative Writing for LGBTQ Youth

23rd, May-26th, May , Zizai Studio, Shanghai

-

LookOUT- Arts Festival on Gender

July 6-15, 2018, Beijing, 798 Art District

-

Let You Be rerun in Beijing Penghao Theatre

26-27th, July , Penghao Theatre, Beijing

-

I Disappear Premiere in Beijing

28th, 29th, July , Penghao Theatre, Beijing

-

Dance Dramaturgy Workshop I

27th,Aug.-2nd, Sep., Free Theatre Alliance Rehearsal Center, Beijing

-

China ComingOUT——Creative Writing for LGBTQ Youth

25th-28th, October , There Art Center, Guangzhou

-

Dance Dramaturgy Workshop II

30th, Oct.-1st, Nov. , Free Theatre Alliance Rehearsal Center

-

MOVING WOR(L)DS – International forum on theatre & migration

7-17th December , Nanjing University, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China

Calendar 2017

-

“When Swallows Cry” South African Premiere Reviews

January, Market Theatre Complex, Newtown Johannesburg Gauteng South Africa

-

Frozen Songs Excerpts Presented at Shanghai Project Chapter 2 Opening

April , Shanghai Himalayas Museum

-

The Returning/ Winterreise with Chinese Cast Premiere in Shanghai

21st-23th, July, Shanghai Huangpu Theatre; 28th-29th, July, Penghao Theatre Beijing

-

I Disappear Stage Reading in Penghao Theatre Beijing

July 26th, 14:30/19:30 Penghao Theatre

-

Frozen Songs Premiere at The Arctic Theatre

September,7th, Tromsø, Norway, Arctic Theatre(Hålogaland Teater )

-

Disco-Teca at STOFF – Stockholm Fringe Festival

9th, September, Teater Tre, Stockholm, Sweden

-

Let You Be Premiere in Beijing

September, 25th-26th, 7:30pm Qinglan Theatre

-

Let You Be Tour in Hangzhou Contemporary Theatre Festival

28th, September, Zhejiang Province Culture Center Small Theatre.

-

Disco-Teca at We Festival of Future Shanghai

October, 7th-8th, No.6 Space, West Bund Camp 3399, Shanghai

-

New Text New Stage II Tatarstan Production Premiere

14th, 15th, 17th, October, 2017, Galiaskar Kamal Tatar National Academic Theatre, Tatarstan

-

New Text New Stage II Chinese/American Production Coming Up

Nov 15th-Dec.10th, Urban Stages Theatre, New York. Sep.24th-30th, Nanjing University, Jiangsu, China.

-

About My Parents and Their Child Touring in Shanghai

December, 9th-10th, Shanghai Dramatic Art Center 1933 Micro Theatre.

-

Contextualizing Dance Dramaturgy – Workshop Series BJ

Dec. 22nd , Goethe Institut China, Beijing

-

Contextualizing Dance Dramaturgy – Workshop Series GZ

Dec. 25th , Ergao Dance Production Group, Guangzhou

-

Contextualizing Dance Dramaturgy – Workshop Series SH

Dec. 30th , Camp 3399 #6 Space, Shanghai

Calendar 2016

-

Night Shift, Beijing rerun

8-9 January, Qinglan theatre, Beijing

-

Ghost 2.0, Beijing rerun

21st-24th, Jan. , Beijing Tianqiao Performing Arts Center

-

SEEDS – A Global Art and Media Project

1-11th, March, Drum Tower West Theatre, Beijing, China

-

Sleeping Beauties—Dancing & Multimedia Workshop Demonstration

6th, March, Drum Tower West Theatre, BJ

-

NEW TEXT, NEW STAGE II – Session 3

20th-26th, March , Guangzhou Dramatic Art Center. There Art Space in GZ

-

Free Theater Alliance – Launch of 1-2-3 Theatre

April, 18th, Qinglan Theater, Beijing

-

Jon Fosse’s Dream of Autumn BOOK LAUNCH

23 April, JEWELVARY Art & Boutique

-

PRACTICAL RETHORIC Workshop (SH)

6月19日, Internet Education Plaza, Shanghai

-

PRACTICAL RETHORIC Open Demonstration (GZ)

July 2, There Art Space, Guangzhou

-

Disco-teca Open Presentation (GZ)

July 9, Guangdong Times Museum, Guangzhou

-

PRACTICAL RETHORIC Open Demonstration(SH)

July 10, RSDBT. Shanghai

-

DISCO-TECA in Shanghai

July 12-13, 1933 Micro Theatre

-

Disco-teca Open Presentation (SH)

July 15, RSDBT, Shanghai

-

In the Field of Hope

July 18-19, Gulou West Theatre

-

About My Parent and Their Child

July23-24, Gulou West Theater · Beijing

-

DISCO-TECA in Beijing

July 23-24, Gulou West Theatre

-

Ghost 2.0 at Wuzhen Theatre Festival

13th, 14th October , Wuzhen, China

-

Workshop by Jon Tombre

12th-13th, November, FTA Rehearsal Space, Beijing

Calendar 2015

-

Practical Rhetoric – Workshop 1

13-18 March, Beijing, Here&Now Studio

-

New Takes on IBSEN

April, 22nd-26th, Shanghai, China

-

Ibsen in One Take – Shanghai 2015

23-24 April, Himalaya Center, Shanghai

-

Night Shift – Norwegian Tour

May 27, 30, Lilehammer, Oslo

-

Practical Rhetoric – Workshop 2

24-28 June, Beijing, Here&Now Studio

-

NEW TEXT, NEW STAGE II – Session 1

13-18 July 2015, Pioneer Theatre, Beijing

-

GHOSTS 2.0

7-9 August, McaM Museum, Shanghai

-

Comedy of Love, Premiere

30th, Sept.-4th, Oct., Penghao Theater, BJ

-

Practical Rhetoric – Workshop 3

3-7 October, Here&Now Studio, Beijing

-

Workshop on Jon Fosse

Oct. 5th-10th , Sheung Wan Municipal Services Building, HK

-

Practical Rhetoric: Launch at Norwegian Embassy

8 October, Norwegian Embassy, Beijing

-

DISCO-TECA, open workshops

10-14 October, Guangzhou

-

Practical Rhetoric:Workshop at Bernard Controls

10 October, Bernard Controls China, Beijing

-

NORA – Norwegian Tour 2015

October 28 - November 3, Bodø; Tromsø; Trondheim

-

DISCO-TECA, premiere

4-5 November, Gender Bender Festival, Bologna

-

Night Shift Guangzhou Tour

13-15th, November, Guangzhou Dramatic Art Center

-

NEW TEXT, NEW STAGE II – Session 2

Nov. 15th-22nd, Shanghai Ming Contemporary Museum, Shanghai Dramatic Art Center

-

Night Shift Shanghai Tour

21-22, November , Shanghai Dramatic Art Center

-

DISCO-TECA: live performances & media feedback

December, 17th, DPAC, Malaysia

Calendar 2014

-

Artists’ Talk Series 1: Architecture and Scenography

January 21 - 27th, Ibsen International Office, Beijing

-

Artists’ Talk Series 1: New Media and Theatre

29th March, Ibsen International Office, Beijing

-

New Texts, New Stage – Session 3

5th - 10th May 2014, Pioneer Theatre, Beijing

-

HEDVIG from the Wild Duck – Oslo

14-16th August, Oslo Opera House, Norway

-

GHOSTS 2.0

6-7 September, Beehive theatre, Beijing

-

Artists’ Talk Series 1: Drama, Communication and Society

7th September, Ibsen International Office, Beijing

-

Ibsen in One Take – Ibsen Festival Oslo

12th September, Oslo,

-

Night Shift – Beijing Fringe Festival

16th-17th September, Beijing Fringe Festival

-

Ibsen in One Take – OzAsia Festival

16-17th September, Adelaide,

-

The phenomenon: Hedda Gabler

11th-12th October, Penghao Theatre, Beijing

-

Night Shift – Beijing Rerun

13th October, Gulou West Theatre. Beijing

-

NORA – World premiere

30-31 October, Tianjin Grand Theatre, Tianjin

-

Jo Strømgren Kompanis at Guandong Modern Dance Festival

November 10-12,2014, Xinghai PA Garden,Guang Zhou, China

-

Jon Fosse’s Blossoms In Shanghai International Contemporary Theatre Festival 2014

November 21-29,2014, Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre, China

Calendar 2013

-

New Texts, New Stage – Session1

16th - 20th April, Star Theatre, Beijing

-

HEDVIG from the Wild Duck

28-29th June, Kwai Tsing Theatre Auditorium, Hong Kong

-

HEDVIG from the Wild Duck – Beijing

23rd July, People Liberation's Army Theatre, Beijing

-

Carcass

26th July 2013, Star Theatre, Beijing

-

Ibsen in One Take – Netherlands

27 - 28th September, Rotterdam

-

Ibsen in One Take – China tour

13 - 16 November, Guangzhou and Shanghai

-

New Texts, New Stage – Session2

23rd November - 1st December, Penghao Theatre, Beijing

-

The Name – Jon Fosse

28 November - 15 December, Shanghai

Calendar 2012

-

The Jon Fosse Project in China

-

The Name

7-11 March, 2012, New Space Theatre, Shanghai

-

Dance Workshop in Beijing with Johannessen for LDTX

13 - 25 April 2012, Beijing

-

Writing Text for Opera

October 11th - 13th 2012, Bergen

-

Field Works

November 22nd - 30th, Macau, Guangzhou, Shenzhen

-

Ibsen in one take

28th November - 1st December, Beijing

-

RETURN _ a devised dance piece

27th November - 6th December, Guangzhou Modern Dance Festival; Singapore Connect Festival.

Calendar 2011

-

Workshop collaboration

23-24 April, Tianqiao Theatre Beijing

-

Masterclass by choreographer Ingun Bjørnsgaard

25 July, Guangzhou

-

Building International Network – seminar Guangdong Moderne Dance Festival

26 July at 11.00, Guangzhou

-

The Name by Jon Fosse, production The New Norwegian Theatre

23 September at 19.15, Venue: The New Stage at Shanghai Theatre Academy, 630 Huashan Rd, Shanghai

-

The Name by Jo Fosse, production The New Norwegian Theatre

24 September at 15 and 19.15, Venue: The New Stage at Shanghai Theatre Academy, 630 Huashan Rd, Shanghai

-

The second Ibsen Festival for Students in China

21 – 23 October, Nanjing

-

The Jon Fosse Project in China

November 4, 2011, 20:00 , The New Space at Shanghai Theatre Acedemy, 630 Huashan Rd., Shanghai, in collaboration with TTS Group

-

International Seminar: Staging Ibsen Today

31 October – 4 November, Beijing

Calendar 2010

-

Ibsen live in China – an exhibition

5 October - 4 November, Hangzhou, Shanghai, Nanjing and Beijing

-

The Lady From the Sea

5 and 6 October 2010, Hangzhou

-

The Lady From the Sea

14 and 15 October, Yi Fu Stage, Shanghai

-

Symposium on Ibsen and Interculturalism in China

15 October, Shanghai Theatre Academy

-

A Doll’s House

22, 23 and 24 October, Capital Theatre, Beijing

-

China International Ibsen Festival for Students

22, 23 and 24 October, Nanjing University

-

Workshop based on Jon Fosse’s work

25 - 29 October, Shanghai Theatre Academy

-

Someone Is Going to Come by Jon Fosse

26 October to 4 November 2010, New Theatre Stage, Shanghai Theatre Academy

-

Ibsen in one take

Wang and Fiskum distilled characters, themes and dialogues from all of Henrik Ibsen’s 27 plays into the life story of one modern Chinese man (…) a lovely play with the laws of film and theatre (…) Ibsen In One Take is Von Trier’s Dogville on a shoestring budget

Theaterkrant, Sept 2013

Premiere (2012): 28th November – 1st December, Troyan Horse Theatre, Beijing

Netherland tour (2013): 27 – 28th September, Festival de Keuze, Rotterdam

China (2013): 13th November, U13 Theater, Guangzhou; 15-16th November, Shanghai Performing Arts Centre, Shanghai.

Norway (2014): 12th Sptember, International Ibsen Festival, Oslo

Australia (2014): 16-17th September, OzAsia Festival, Adelaide

China (2015): 23-24th April, Himalayan Cultural Centre, Shanghai

Ibsen in One Take is neither a medley of Ibsen’s masterpieces nor an original pièce inspired by Ibsen’s work. It is both these things, and more.

Born of the collaboration of up-and-coming Chinese director Wang Chong and Beijing-based Norwegian playwright Oda Fiskum, Ibsen in One Take is a bold attempt to rework the Ibsenian tradition into a piece of new writing. The result is a combination of classics and novelty, a slice-of-life from a contemporary Chinese man’s existence which also reverberates with the echoes of Ibsen’s philosophical and moral dilemmas. In producer Inger Buresund’s words, a “modern Chinese story told in a contemporary yet universal way”.

Ibsen in One Take follows an old man who is spending his last days in a hospital room. As the play unfolds, the man embarks on an introspective journey into his past and reminisces about his childhood and youth, his marriage and love affairs, the turning points as well as the shortcomings in his life. Throughout this reminiscence, the man, haunted by his private ghosts, confronts his regrets and tries to make sense of his existence and unanswered questions.

The production is the result of a 6 months-long work which firstly proceeded on parallel tracks and was then assembled and reworked during rehearsals. Director Wang Chong ideated the original storyline and handed it to Fiskum, who compiled the script enriching the plot with numerous quotes and references from Ibsen’s plays (like A Doll’s House, Ghosts, Peer Gynt, Master Builder and more). The creative duo then pieced the parts together, supported throughout the process by Hege Randi Tørressen, dramaturge of Oslo’s Nationaltheatret.

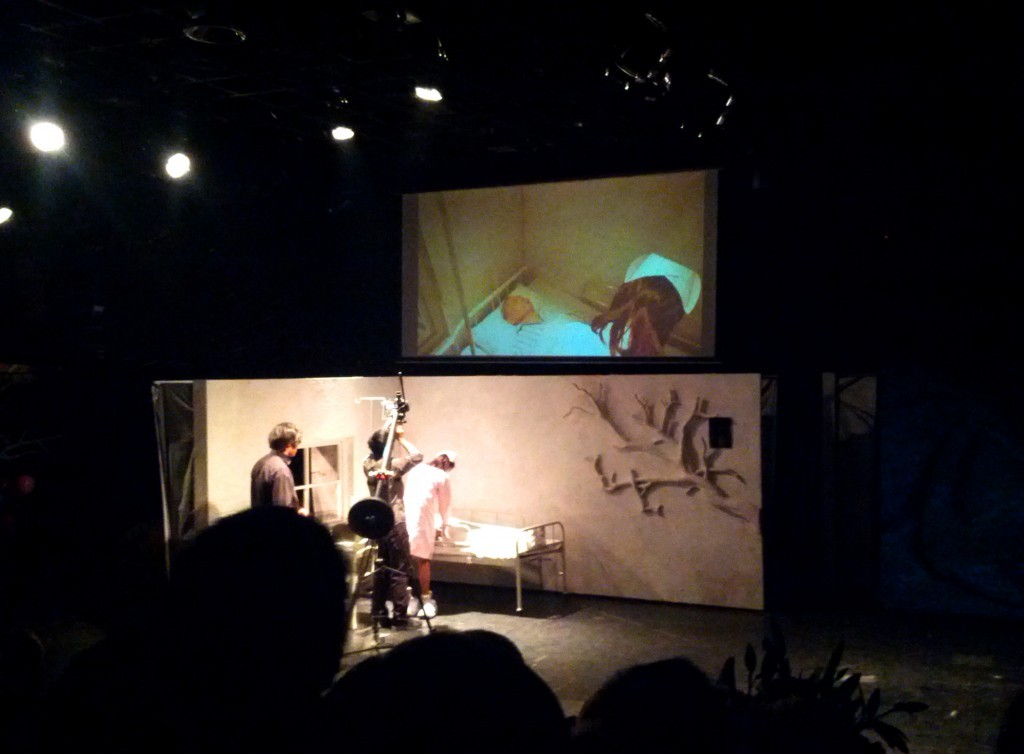

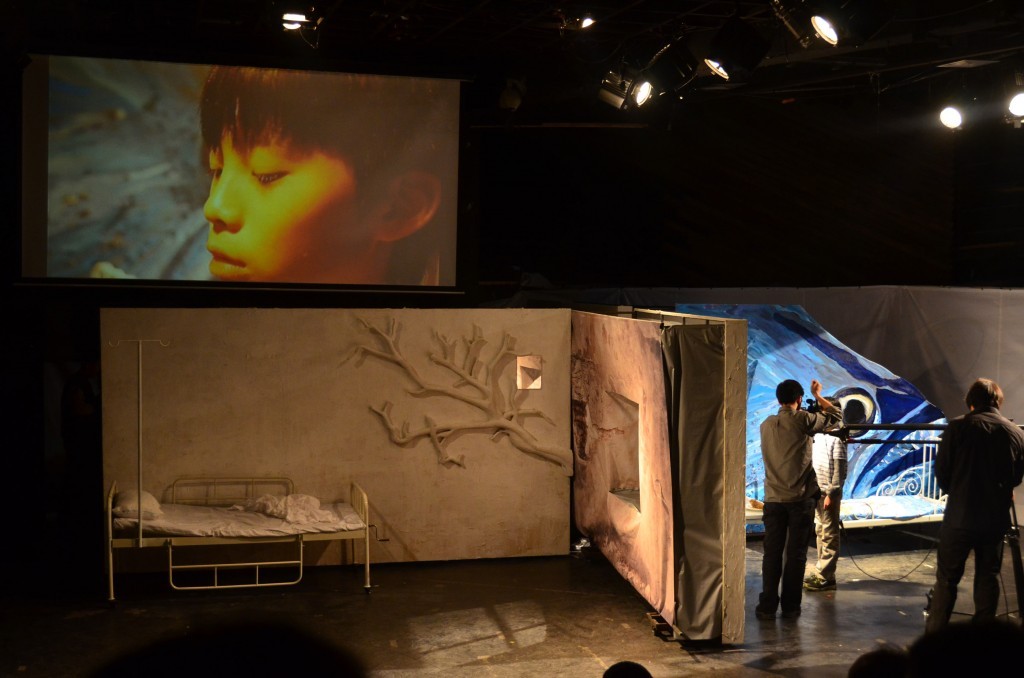

A remarkably innovative trait of the pièce lies in its dramatic structure, which represents a further development of Wang ’s previous experiments with live video-recording on stage: the whole performance is filmed by a cinematic troupe who follows the actors around the stage, and projected in real time on a big screen right above the stage. Hence the performance’s name: the “one take” of the title is an actual camera take which captures the stage action from beginning to end, without any editing or montage. This dramatic device allows the audience to focus on either the stage action or its filmic rendition at will. What’s more, the free play of the two levels (stage action and film) generates an extra, self-referential layer (the filming of the stage action). The performance, in other words, is structured along different layers which continuously interact and question each other in terms of authenticity, artistic medium and emotional response.

Commissioned by Ibsen International for the project Ibsen in China 2012 in collaboration with The Norwegian Embassy in Beijing and The Norwegian Consulates General in Shanghai and Guangzhou. Produced by Théatre du Rêve Expérimental

CREDITS:

Script: Oda Fiskum

Director: Wang Chong

Assistant Directors: Liang Anzheng, Yang Fan

Director of Photography: Ding Yi

Dramaturge: Hege Randi Tørressen

Chinese Producer (2012): Li Yi

Norwegian Producer: Inger Buresund

Executive Producers: Fabrizio Massini, Liu Chen, Li Xiaoxi

Set Designer (2012): Li Yi

Set Designer (2013): Dou Hui

Costume Designer: Jin Ran

Sound Designer: Zhang Yuelong

Composer: Li Yangfan

Lighting Designer: Liu Shuchang

Stage Manager: Liu Mizhuang

- Li Jialong – Him as a young man, Him as an adult

- Tan Zongyuan – Him as an old man

- Yang Boxiong – Him as a child

- Liu Xiaqing – Father

- Fang Li – Mother

- Zhang Yang – Girlfriend, Nurse

- Zhao Hongwei – Wife

- Man Ting – Girl with pigtails

Performance photos:

Modern China trhough a lovely Ibsen-filter

REVIEW by Joost Ramaer

![]()

original review in Dutch posted on “Theaterkrant” _ read original

A boy lies on his back on stage. He cuts origami figures from a sheet of pink paper. A screen of white cloth separates him from his parents, who talk about him behind the screen. While acting, the actors are being filmed by a team of camera men. Their images appear live on a big screen above the stage. On the screen it seems as if the boy lies on the ground in front of his parents. The contrast between the film image and the setting on stage suggests that the talking parents only exist in the boy’s imagination.

Ibsen In One Take is the fruit of a remarkable cooperation between the Chinese theatre director Wang Chong and the Norwegian stagewright Oda Fiskum. The show enjoyed its Dutch premiere during festival De Keuze (The Choice) of the Rotterdamse Schouwburg (the city theatre of Rotterdam). Wang and Fiskum distilled characters, themes and dialogues from all of Henrik Ibsen’s 27 plays into the life story of one modern Chinese man. We see him as a little boy, as a young man and at the end of his life. Ibsen In One Take has the form of a retrospective: old, ill and weakened, the man sees his life draw past him in a series of flashbacks. The last three words of the title refer to the filmed half of the show, shot live and in one sweeping take without a single interruption, let alone any editing. Of course, they also refer to the new jigsaw puzzle Wang and Fiskum have laid out of all those hundreds of little Ibsen-pieces.

By combining film and acting Wang has doubled the space for his own imagination, and therefore also for ours. What we see on stage, continuously and simultaneously gets a different meaning on screen. Lovely is a scene early on in the play, when the man as a boy squats on the floor while his father scolds him. At first he shouts in the boy’s face. Then, suddenly, the boy changes position, but the father keeps scolding in the direction of the spot the boy has just left. On screen, however, they still seem to be looking each other in the eye. Normally it is the film director who edits separate scenes, shot at different places and times, into one fluid whole. In the scolding sequence Wang creates the separate scenes on stage – a lovely play with the laws of film and theatre.

The story of the show is of all times. The man grows up at the mercy of his father’s inability to forge an emotional bond with his son. When he receives his colleagues from work at his home, the boy is wheeled out like a circus animal, to show off his feeble mastery of the recorder. The moment they have left, his father scolds him again: ‘You know I hate the sound of that thing!’ This upbringing leads unavoidably to a failed marriage – the man cannot give what his father withheld from him. His relationship stays childless. His wife wants to leave him, but cannot bring herself to take the leap. The man ends up alone in a hospital bed, terrorised by a rude nurse. A girl with coloured balloons appears, the symbolic messenger of the nearing end of his life.

The emotional handicaps, the not-listening, the not-seeing, the indecisiveness of the characters – it is all painfully recognisable Ibsen. But with the help of his two dimensions, Wang also sculpts this material, just as recognisably, into present day China. Children who see their own way blocked by the ancient Chinese tradition that they should take care of their parents when they become old and needy. The economic necessity forcing them to work night and day, causing estrangement from their loved ones.

The ultraquick changes of clothes and position by the actors, the camera men trucking around with their equipment: next to the show itself, the simple means with which Wang has created it are constantly in full view for the audience. That gives it a vulnerable quality, stirring and touching in equal measure. Ibsen In One Take is Von Trier’s Dogville on a shoestring budget. The only uneasy aspect is the music by Zhang Yuelong. It is very beautiful, but also very loud.

The end is wonderful. The old man sees himself, and the other people he shared his life with, loom up one last time in circles of light. The moment he tries to hug them, they disappear in the darkness. White smoke envelops the stage. The circles of light merge into a path, allowing the old man to walk to his death.