-

Calendar 2024

Calendar 2023

Calendar 2022

Calendar 2021

Calendar 2020

-

Children of Ginko – Preview

31 October, Shanghai

-

Children of Ginko – Premiere

7-8 November, Shanghai,

Calendar 2019

-

Dance Dramaturgy 2.1

23-23 April, Aosai Space, Dali

-

New Text New Stage – “A Deal” Australian Premiere

23-31 August, Sydney

Calendar 2018

-

Web Traffic — A Multimedia Dance Theatre

Jan.5-7th , Shanghai International Dance Center

-

China ComingOUT – Creative Writing for LGBTQ Youth

31st Jan.-4th Feb. , Destination, Beijing.

-

SPEAK OUT: #1 LGBTQ&Perfromance BJ

7th, April , Italian Institute of Culture, Beijing

-

SPEAK OUT: #2 Performance&Performativity

8th, April , Xiaozhong Bookstore, Beijing

-

SPEAK OUT: #1 LGBTQ&Perfromance SH

10th, April , NEXTMIXING, Shanghai

-

SPEAK OUT: #1 LGBTQ&Perfromance GZ

12th, April , Ergao Dance Production Group, Guangzhou

-

SPEAK OUT : #3 Gender, Documentary and Activism

19th, May, Bookworm, Beijing

-

China ComingOUT – Creative Writing for LGBTQ Youth

23rd, May-26th, May , Zizai Studio, Shanghai

-

LookOUT- Arts Festival on Gender

July 6-15, 2018, Beijing, 798 Art District

-

Let You Be rerun in Beijing Penghao Theatre

26-27th, July , Penghao Theatre, Beijing

-

I Disappear Premiere in Beijing

28th, 29th, July , Penghao Theatre, Beijing

-

Dance Dramaturgy Workshop I

27th,Aug.-2nd, Sep., Free Theatre Alliance Rehearsal Center, Beijing

-

China ComingOUT——Creative Writing for LGBTQ Youth

25th-28th, October , There Art Center, Guangzhou

-

Dance Dramaturgy Workshop II

30th, Oct.-1st, Nov. , Free Theatre Alliance Rehearsal Center

-

MOVING WOR(L)DS – International forum on theatre & migration

7-17th December , Nanjing University, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China

Calendar 2017

-

“When Swallows Cry” South African Premiere Reviews

January, Market Theatre Complex, Newtown Johannesburg Gauteng South Africa

-

Frozen Songs Excerpts Presented at Shanghai Project Chapter 2 Opening

April , Shanghai Himalayas Museum

-

The Returning/ Winterreise with Chinese Cast Premiere in Shanghai

21st-23th, July, Shanghai Huangpu Theatre; 28th-29th, July, Penghao Theatre Beijing

-

I Disappear Stage Reading in Penghao Theatre Beijing

July 26th, 14:30/19:30 Penghao Theatre

-

Frozen Songs Premiere at The Arctic Theatre

September,7th, Tromsø, Norway, Arctic Theatre(Hålogaland Teater )

-

Disco-Teca at STOFF – Stockholm Fringe Festival

9th, September, Teater Tre, Stockholm, Sweden

-

Let You Be Premiere in Beijing

September, 25th-26th, 7:30pm Qinglan Theatre

-

Let You Be Tour in Hangzhou Contemporary Theatre Festival

28th, September, Zhejiang Province Culture Center Small Theatre.

-

Disco-Teca at We Festival of Future Shanghai

October, 7th-8th, No.6 Space, West Bund Camp 3399, Shanghai

-

New Text New Stage II Tatarstan Production Premiere

14th, 15th, 17th, October, 2017, Galiaskar Kamal Tatar National Academic Theatre, Tatarstan

-

New Text New Stage II Chinese/American Production Coming Up

Nov 15th-Dec.10th, Urban Stages Theatre, New York. Sep.24th-30th, Nanjing University, Jiangsu, China.

-

About My Parents and Their Child Touring in Shanghai

December, 9th-10th, Shanghai Dramatic Art Center 1933 Micro Theatre.

-

Contextualizing Dance Dramaturgy – Workshop Series BJ

Dec. 22nd , Goethe Institut China, Beijing

-

Contextualizing Dance Dramaturgy – Workshop Series GZ

Dec. 25th , Ergao Dance Production Group, Guangzhou

-

Contextualizing Dance Dramaturgy – Workshop Series SH

Dec. 30th , Camp 3399 #6 Space, Shanghai

Calendar 2016

-

Night Shift, Beijing rerun

8-9 January, Qinglan theatre, Beijing

-

Ghost 2.0, Beijing rerun

21st-24th, Jan. , Beijing Tianqiao Performing Arts Center

-

SEEDS – A Global Art and Media Project

1-11th, March, Drum Tower West Theatre, Beijing, China

-

Sleeping Beauties—Dancing & Multimedia Workshop Demonstration

6th, March, Drum Tower West Theatre, BJ

-

NEW TEXT, NEW STAGE II – Session 3

20th-26th, March , Guangzhou Dramatic Art Center. There Art Space in GZ

-

Free Theater Alliance – Launch of 1-2-3 Theatre

April, 18th, Qinglan Theater, Beijing

-

Jon Fosse’s Dream of Autumn BOOK LAUNCH

23 April, JEWELVARY Art & Boutique

-

PRACTICAL RETHORIC Workshop (SH)

6月19日, Internet Education Plaza, Shanghai

-

PRACTICAL RETHORIC Open Demonstration (GZ)

July 2, There Art Space, Guangzhou

-

Disco-teca Open Presentation (GZ)

July 9, Guangdong Times Museum, Guangzhou

-

PRACTICAL RETHORIC Open Demonstration(SH)

July 10, RSDBT. Shanghai

-

DISCO-TECA in Shanghai

July 12-13, 1933 Micro Theatre

-

Disco-teca Open Presentation (SH)

July 15, RSDBT, Shanghai

-

In the Field of Hope

July 18-19, Gulou West Theatre

-

About My Parent and Their Child

July23-24, Gulou West Theater · Beijing

-

DISCO-TECA in Beijing

July 23-24, Gulou West Theatre

-

Ghost 2.0 at Wuzhen Theatre Festival

13th, 14th October , Wuzhen, China

-

Workshop by Jon Tombre

12th-13th, November, FTA Rehearsal Space, Beijing

Calendar 2015

-

Practical Rhetoric – Workshop 1

13-18 March, Beijing, Here&Now Studio

-

New Takes on IBSEN

April, 22nd-26th, Shanghai, China

-

Ibsen in One Take – Shanghai 2015

23-24 April, Himalaya Center, Shanghai

-

Night Shift – Norwegian Tour

May 27, 30, Lilehammer, Oslo

-

Practical Rhetoric – Workshop 2

24-28 June, Beijing, Here&Now Studio

-

NEW TEXT, NEW STAGE II – Session 1

13-18 July 2015, Pioneer Theatre, Beijing

-

GHOSTS 2.0

7-9 August, McaM Museum, Shanghai

-

Comedy of Love, Premiere

30th, Sept.-4th, Oct., Penghao Theater, BJ

-

Practical Rhetoric – Workshop 3

3-7 October, Here&Now Studio, Beijing

-

Workshop on Jon Fosse

Oct. 5th-10th , Sheung Wan Municipal Services Building, HK

-

Practical Rhetoric: Launch at Norwegian Embassy

8 October, Norwegian Embassy, Beijing

-

DISCO-TECA, open workshops

10-14 October, Guangzhou

-

Practical Rhetoric:Workshop at Bernard Controls

10 October, Bernard Controls China, Beijing

-

NORA – Norwegian Tour 2015

October 28 - November 3, Bodø; Tromsø; Trondheim

-

DISCO-TECA, premiere

4-5 November, Gender Bender Festival, Bologna

-

Night Shift Guangzhou Tour

13-15th, November, Guangzhou Dramatic Art Center

-

NEW TEXT, NEW STAGE II – Session 2

Nov. 15th-22nd, Shanghai Ming Contemporary Museum, Shanghai Dramatic Art Center

-

Night Shift Shanghai Tour

21-22, November , Shanghai Dramatic Art Center

-

DISCO-TECA: live performances & media feedback

December, 17th, DPAC, Malaysia

Calendar 2014

-

Artists’ Talk Series 1: Architecture and Scenography

January 21 - 27th, Ibsen International Office, Beijing

-

Artists’ Talk Series 1: New Media and Theatre

29th March, Ibsen International Office, Beijing

-

New Texts, New Stage – Session 3

5th - 10th May 2014, Pioneer Theatre, Beijing

-

HEDVIG from the Wild Duck – Oslo

14-16th August, Oslo Opera House, Norway

-

GHOSTS 2.0

6-7 September, Beehive theatre, Beijing

-

Artists’ Talk Series 1: Drama, Communication and Society

7th September, Ibsen International Office, Beijing

-

Ibsen in One Take – Ibsen Festival Oslo

12th September, Oslo,

-

Night Shift – Beijing Fringe Festival

16th-17th September, Beijing Fringe Festival

-

Ibsen in One Take – OzAsia Festival

16-17th September, Adelaide,

-

The phenomenon: Hedda Gabler

11th-12th October, Penghao Theatre, Beijing

-

Night Shift – Beijing Rerun

13th October, Gulou West Theatre. Beijing

-

NORA – World premiere

30-31 October, Tianjin Grand Theatre, Tianjin

-

Jo Strømgren Kompanis at Guandong Modern Dance Festival

November 10-12,2014, Xinghai PA Garden,Guang Zhou, China

-

Jon Fosse’s Blossoms In Shanghai International Contemporary Theatre Festival 2014

November 21-29,2014, Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre, China

Calendar 2013

-

New Texts, New Stage – Session1

16th - 20th April, Star Theatre, Beijing

-

HEDVIG from the Wild Duck

28-29th June, Kwai Tsing Theatre Auditorium, Hong Kong

-

HEDVIG from the Wild Duck – Beijing

23rd July, People Liberation's Army Theatre, Beijing

-

Carcass

26th July 2013, Star Theatre, Beijing

-

Ibsen in One Take – Netherlands

27 - 28th September, Rotterdam

-

Ibsen in One Take – China tour

13 - 16 November, Guangzhou and Shanghai

-

New Texts, New Stage – Session2

23rd November - 1st December, Penghao Theatre, Beijing

-

The Name – Jon Fosse

28 November - 15 December, Shanghai

Calendar 2012

-

The Jon Fosse Project in China

-

The Name

7-11 March, 2012, New Space Theatre, Shanghai

-

Dance Workshop in Beijing with Johannessen for LDTX

13 - 25 April 2012, Beijing

-

Writing Text for Opera

October 11th - 13th 2012, Bergen

-

Field Works

November 22nd - 30th, Macau, Guangzhou, Shenzhen

-

Ibsen in one take

28th November - 1st December, Beijing

-

RETURN _ a devised dance piece

27th November - 6th December, Guangzhou Modern Dance Festival; Singapore Connect Festival.

Calendar 2011

-

Workshop collaboration

23-24 April, Tianqiao Theatre Beijing

-

Masterclass by choreographer Ingun Bjørnsgaard

25 July, Guangzhou

-

Building International Network – seminar Guangdong Moderne Dance Festival

26 July at 11.00, Guangzhou

-

The Name by Jon Fosse, production The New Norwegian Theatre

23 September at 19.15, Venue: The New Stage at Shanghai Theatre Academy, 630 Huashan Rd, Shanghai

-

The Name by Jo Fosse, production The New Norwegian Theatre

24 September at 15 and 19.15, Venue: The New Stage at Shanghai Theatre Academy, 630 Huashan Rd, Shanghai

-

The second Ibsen Festival for Students in China

21 – 23 October, Nanjing

-

The Jon Fosse Project in China

November 4, 2011, 20:00 , The New Space at Shanghai Theatre Acedemy, 630 Huashan Rd., Shanghai, in collaboration with TTS Group

-

International Seminar: Staging Ibsen Today

31 October – 4 November, Beijing

Calendar 2010

-

Ibsen live in China – an exhibition

5 October - 4 November, Hangzhou, Shanghai, Nanjing and Beijing

-

The Lady From the Sea

5 and 6 October 2010, Hangzhou

-

The Lady From the Sea

14 and 15 October, Yi Fu Stage, Shanghai

-

Symposium on Ibsen and Interculturalism in China

15 October, Shanghai Theatre Academy

-

A Doll’s House

22, 23 and 24 October, Capital Theatre, Beijing

-

China International Ibsen Festival for Students

22, 23 and 24 October, Nanjing University

-

Workshop based on Jon Fosse’s work

25 - 29 October, Shanghai Theatre Academy

-

Someone Is Going to Come by Jon Fosse

26 October to 4 November 2010, New Theatre Stage, Shanghai Theatre Academy

-

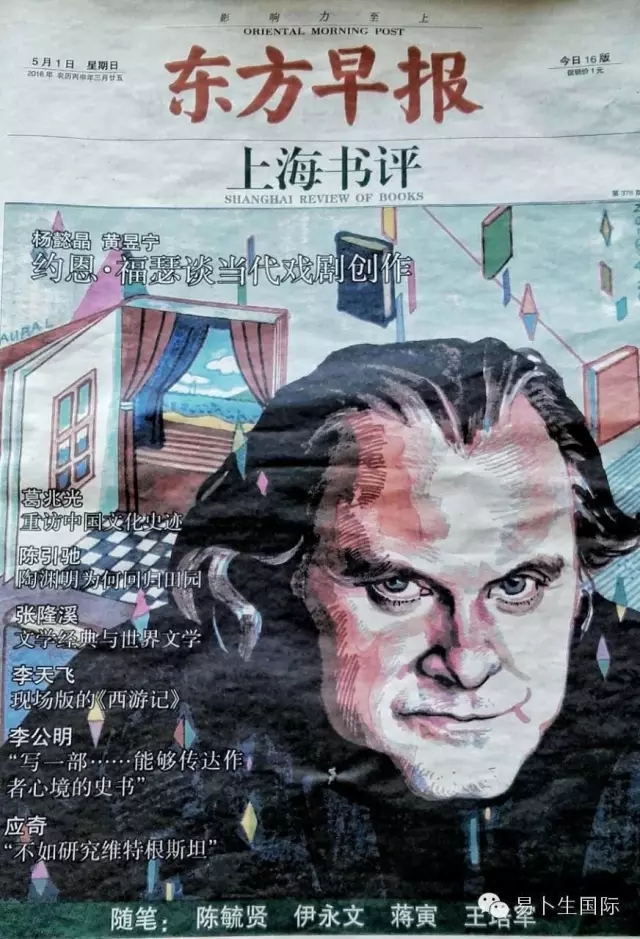

Dream of Autumn BOOK LAUNCH

JON FOSSE AND CHINA

Volume Ⅰ of Jon Fosse’s collected plays Someone is Going to Come, published in 2014, was a great success and created interest in theatre circles in the Chinese speaking world. On April 23, Volume Ⅱ- Dream of Autumn has been released in Chinese, and Volume Ⅲ is on its way.

This is the last achievement of the program ‘Fosse in China’, launched by Ibsen  International in 2010, for the translation, circulation and production of Jon Fosse’s dramatic works in China. Since its launch, the program included the translation of 8 plays, several workshop in collaboration with Shanghai Theatre Academy, three local productions by Shanghai’s SDAC and Fujian’s People Theatre’s Company, and the international festival Jon Fosse’s Blossoms.

International in 2010, for the translation, circulation and production of Jon Fosse’s dramatic works in China. Since its launch, the program included the translation of 8 plays, several workshop in collaboration with Shanghai Theatre Academy, three local productions by Shanghai’s SDAC and Fujian’s People Theatre’s Company, and the international festival Jon Fosse’s Blossoms.

Within a few years’ time, the appearance of Fosse’s works on the Chinese stage has

become somewhat of a phenomenon. The sales’ of volume I have surpassed any expectation. Theatre companies, from Beijing to Hong Kong, have organized activities and events dedicated to the playwright. The press, from Oriental Morning Post to the English language Global Times dedicated in-depth reviews and monographic articles (see Translation of Jon Fosse play mesmerizes readers of China). And Chinese academics started to follow with close interest Fosse’s work too.

To open a wider discussion around Fosse’s dramatic work, we publish (below in this page) an essay by prof. Guo Chenzi about the staging of Fosse in China.

BOOK LAUNCH OF VOLUME 2

Royal Norwegian Consulate General’s Consul General, Øyvind Stokke, delivered an  opening speech. After reading an excerpt in Norwegian to let the audience hear the original sound of Fosse’s writing, Mr. Stokke addressed the audience: “In my view there is a unique mood or atmosphere in his works, a rhythm. Many things are not expressed, by words I mean, and some things are often repeated. Fosse creates a line or space in his plays- and so on the stage- that is sometimes tense or worrying, but there is also movement in the room, people brought together, episodes from the past brought to light. Quietness and nature, distance and relations between human beings, Jon Fosse has created a room on his own, and for his works in the world, and a room for us, the readers. And now, in China, the room expands.”

opening speech. After reading an excerpt in Norwegian to let the audience hear the original sound of Fosse’s writing, Mr. Stokke addressed the audience: “In my view there is a unique mood or atmosphere in his works, a rhythm. Many things are not expressed, by words I mean, and some things are often repeated. Fosse creates a line or space in his plays- and so on the stage- that is sometimes tense or worrying, but there is also movement in the room, people brought together, episodes from the past brought to light. Quietness and nature, distance and relations between human beings, Jon Fosse has created a room on his own, and for his works in the world, and a room for us, the readers. And now, in China, the room expands.”

Ibsen International’s Artistic Director, Fabrizio Massini, addressed Fosse’s influence and international success. “By drying out the language and clearing the script of references, he forced the actors and the spectators to dig deeper. Fosse asks an effort of us, to understand what his characters are troubled by, what they are fighting with, what are their hopes. The universal questions of mortality, of love, of pain, are sketched very subtly, like silhouettes that our imagination and our empathy need to fill out… This book launch is a perfect example of the intercultural value of Fosse’s writing, and of the fantastic time of global cultural exchange we are living in. As an Italian theatre practitioner, who was touched watching Fosse’s plays in Italy in 15 years ago, to give my contribution to promote his work in China is a great honor.”

Ibsen International’s Artistic Director, Fabrizio Massini, addressed Fosse’s influence and international success. “By drying out the language and clearing the script of references, he forced the actors and the spectators to dig deeper. Fosse asks an effort of us, to understand what his characters are troubled by, what they are fighting with, what are their hopes. The universal questions of mortality, of love, of pain, are sketched very subtly, like silhouettes that our imagination and our empathy need to fill out… This book launch is a perfect example of the intercultural value of Fosse’s writing, and of the fantastic time of global cultural exchange we are living in. As an Italian theatre practitioner, who was touched watching Fosse’s plays in Italy in 15 years ago, to give my contribution to promote his work in China is a great honor.”

The translator, Lulu Zou, professor at Shanghai Theatre Academy, and researcher of western theatre and literature, told about her 10-years-long efforts to the translation of. Jon Fosse’s works. In her opinion, translation work for her resembles an extremely deep exchange with the author. Quoting the song writer Leonard Cohen, although Fosse’s works tackle the universal fragility and desperation shared by human beings there is a light coming out of the cracks. It is this light, this hope and strength which she likes to share with the Chinese readers.

The translator, Lulu Zou, professor at Shanghai Theatre Academy, and researcher of western theatre and literature, told about her 10-years-long efforts to the translation of. Jon Fosse’s works. In her opinion, translation work for her resembles an extremely deep exchange with the author. Quoting the song writer Leonard Cohen, although Fosse’s works tackle the universal fragility and desperation shared by human beings there is a light coming out of the cracks. It is this light, this hope and strength which she likes to share with the Chinese readers.

In the end, V+ Theatre read an excerpt from the play Dream of Autumn.

Fosse has come

by Guo Chenzi

Fosse has come. It was not the first time for Fosse to come to China. [The magazines] Dramatic Arts and Shanghai Theatre published the translations of “Someone is going to come”and “A Summer’s Day”. Shanghai Theater Academy and Shanghai Dramatic Arts Center also staged productions of “Someone is going to come” and “The Name”. However, this time Fosse has arrived in a different fashion at the Shanghai International Contemporary Theatre Festival, hosted by Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre, with five theatre groups from different countries staging a different repertoire from Fosse, like a retrospective in a film festival or a monographic review.

Dramatic Arts and Shanghai Theatre published the translations of “Someone is going to come”and “A Summer’s Day”. Shanghai Theater Academy and Shanghai Dramatic Arts Center also staged productions of “Someone is going to come” and “The Name”. However, this time Fosse has arrived in a different fashion at the Shanghai International Contemporary Theatre Festival, hosted by Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre, with five theatre groups from different countries staging a different repertoire from Fosse, like a retrospective in a film festival or a monographic review.

Fosse has come. It doesn’t seem the Fosse based in Bergen, but a playwright forged by countless generations, genres and styles of European play writing, although his plays are so subtle, even flat. His recognition and definition as a successor of Ibsen, Pinter and Beckett is widely accepted, and indeed appropriate. Ibsen? Certainly so, as can be observed in “Death Variations” performed by the Indian Surnai Theatre Group from Mumbai. The daughter’s suicide makes it hard for the couple to keep living. As a young couple, their love was a scorching flame that not even their parents’ opposition could stop from burning, nor could poverty stop them from marrying and have a child. However, as the routine infiltrates their life, the intensity of their relationship slowly diminishes. The passion retreats, followed by the husband’s infidelity, then separation, and divorce.Their daughter ends up being a misfit, and finally chooses to end her own life. The focus on society, family and gender relations are a little Ibsenian. And sois the image of the handsome and sweet man, working as object of desire for the daughter, as well as a symbol of death. Let us not forget that Ibsen wroteseveral plays coloured with the hues of symbolism.

The silhouettes of Beckett and Pinter are more apparent. Fo rinstance, in “I am the wind” brought by Intercity Festival (Italy). Two men decide to sail on the sea. One man insisted to sail into the vast unknown of the ocean, while the other falls prey to fear. One throws himself in the water with excitement, the other is taken by terror and looses his way. Are they variations of Vladimir and Estragon? Yes and no. The musicality of Italian language gives rhythm and movement to the script. There is a similar linguistic flavour in the continuous questions and repetition that remind of Beckett, but in comparison with “Waiting for Godot”, the object and the nature of the investigation are different. They do not shoulder the burden of philosophical propositions, but face life more directly. From Pinter, Fosse borrows the rich subtext. Like a French chef, who not only masters the recipe and the ingredients but also the artistry of matching the cutlery, the food is placed on the plate, but it is within the large white background of the table that the meaning is constructed. In “A Summer’s Day” by Kamal Theatre from Tatarstan, Russia, the husband decides to set sail. The wife is restless and senses the subtle cracks wrecking their relationship. In her recollection of the old days, several years later, we find Pinter-style repetitions of daily language. Daily enough, subtle enough, enough to resemble the Pinter-style “hidden menace”. Did the husband have an affair with the wife’s friend? Yes and no, just like in Pinter’s “Old Times”.

Fosse’s fascination with the ocean brings a sense of loneliness; it is regarded like fate, like a symbol of an indomitable and unpredictable fate, regarded as the ultimate ownership of happiness. In Fosse’s world, eachperson is a lonely island, looking at each yet apart from each other.

Is Fosse’s work a pastiche? In his plays elements from Ibsen, Beckett, and Pinter interweave. Or, in other terms, all the concerns of modernism such as the solitude, the difficulty to communicate, the collapse of the family entity, the death wish…in Fosse’s work find a new formulation. Compared to Ibsen, Fosse makes a further step from narrative and theatricality; compared to Beckett, he moves away from metaphysics; compared to Pinter, his world is not as vague and ambiguous. The inspiration he gives is that the rules of playwrighting have long changed, Ibsen’s symbolism has been decrypted long ago, and Beckett and Pinter aren’t part of the rebellious avant-garde anylonger, but are now to be considered classics. The tradition of modernist theatre that he picks up did not die after the peak of absurdism, but is transformed into a new legacy, which is enriched by his creation.

Fosse’s arrival to China triggered a new discussion. While venturing into such depths, the discussion is brought back to common sense, about “what does he write about” and “how does he write it”. Regarding the “what”, is the dilemmas of mental hilliness,the anxiety of the soul, the restlessness of life, the answerless journey in search of an answer, the crave to communicate and the difficulty to reach out to each other. It is not on about social topics and it does not dwell on the surface of events. About the “how”, one hundred years of theatrical reform did not come for nothing, and some ossified “golden rules” are entirely abandoned. For instance in “Death Variation” and “A Summer’s Day” almost half of the play is occupied with the memory of the past, like flashbacks in a film. When the audience is presented with a journey into old memories, the past presents itself as a flashback, but the protagonists remain on stage, as witnesses, thus creating an opposite relation between past and present. The protagonist observes the scene, sometimes even intervenes, but hardly manages to change the direction or the ending. In “A Summer’s Day” two French windows divide the front stage from the back. A younger and an older actress stand on opposite sides. When one performs, the other watches through the window, still yet emotionally engaged, unable to communicate, or as if communication would be no use. In “Death Variations” the divorced couple reunites after many years due to the daughter’s suicide. Once again they fight, once again they fall into silence. Their grief may be shared, but facing their beloved’s death together won’t change their relationship. They occupy the right side of the stage, while center stage is another version of the couple, young and deeply in love, sharing their tender feelings for each other. Yet, it is the same couple. How did this change happen? Fosse is not interested in sketching a play where the characters’ emotion drives the plot, instead he displays on the stage how life events happen, without much emphasis. Moreover, the productions cannot escape the poetic and concise language of the text. In “I am the wind”, the whole stage is empty with the only exception being the stage, covered with the fragments of a broken mirror. The physical language of the two actors and the stage effects are reduced to minimum. The audience is left with the only impression of two people standing side by side, moving rhythmically along with the waves of the ocean. That is enough. The empty space resembles the sea, and emptiness is expectancy in theatre. It is another language. The empty space emphasizes the actors’ body language and rhythm, thus the whole production acquires musicality.

In these times, when the contemporary Chinese theatre scene doesn’t often display signs of postmodernity, Fosse and many foreign directors have suffered similar controversies. Which demonstrates that we haven’t passedthe gate of modernism yet. Compared to other adapted productions by Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre such as Yasmina Reza’s“Art” and “God of Carnage”,David Greig’s “Midsummer”, David Mamet’s “Oleanna”, Patrick Marber’s “Closer”, Sarah Kane’s “4.48 PSYCHOSIS” and Fosse’s “The Name”, compared to these modern playwrights’ works, should the [Chinese] playwrights stop at TV-series-inspired logic and style?

Fosse has come. Has he come for nothing? I hope not.

Originally published in SHANGHAI Theatre, 2015, issue 1

Reprinted in Guo Chenzi’s collected essays “The Curtain Draws Open – Theatre Review” (Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House, 2015).

English translation by: FM, CZ